Glory & Gratitude in Shenandoah National Park (by Mike Baker)

"The Shenandoah you see today is a complex mixture of human history and natural forces–the result of the life and times of the nation that owns it," reads a display at The Byrd Visitor Center in Shenandoah National Park.

When one visits Shenandoah National Park, experiences its beauty, and learns how it came to be, it's hard not to be deeply grateful for such a place. The park's solitude and serenity, existing in such close proximity to our nation's capitol, did not happen by accident. Shenandoah as we know it today is the result of men and women who sacrificed their time, careers, and even lives to make this one of America's most beautiful parks.

Settlers first came to the Blue Ridge Mountains during the 18th century and lived off the land in small homesteads for generations in remote hollows and ridgetops while the eastern seaboard grew in population. As the parks of the west grew in prominence, the desire for a park near to Washington D.C. also grew, even though the uplifted granite and basalt bedrock had been waiting for over one billion years.

The "single greatest feature" of the park is Skyline Drive, a 105-mile winding road from Rockfish Gap in the south to Front Royal in the north. Largely built by the Civilian Conservation Corps "boys" starting in 1933, its construction provided hundreds of jobs that eased the sting of the Great Depression. With 75 scenic overlooks that provide views eastward of rolling hills and the valley westward, the 35-mph speed limit ensures a leisurely drive as well as being able to see the forest as well as the trees.

One of the park's notable geologic features are its talus formations, rocky outcrops caused by the freeze-thaw cycle that break off pieces of rock and produce a "rock river" that flows down the mountainside at an imperceptibly slow pace, providing a beneficial ecosystem—growth surface for lichens, shelter for rodents and reptiles, and ambush stands for bobcats.

If Skyline Drive is the main artery through the park, Big Meadows is its heart. During October, the meadow's paths are full of Wooly Bear Caterpillars seeking shelter before the onset of winter. Renowned for the folklore surrounding them, the insect's coloring is thought in local custom to predict the harshness of winter. This little fellow's somewhat large black area may indicate a tough winter while the broader brown area may not!

The Byrd Visitor Center has an informative display that tells the story of how the park came to be, including stories of individuals and families who were forced to vacate their property via the U.S. government's employment of eminent domain. Portrayed originally as isolated "hillbillies" by park advocates seeking to "modernize" the region, the local population who vacated the thousands of private tracts of land left behind evidence– Coca Cola bottles, stamped metal toy "ray guns", and Band Aids– that marked them as fully integrated into current American culture despite the story told to the public.

Park rangers at Byrd Visitor Center conduct engaging talks about black bears, passing along samples of hair while dispelling often-held myths about them. One myth is that black bears are not as competent running uphill as they are downhill. According to rangers, it is not uncommon to see young black bears chase hopelessly after a deer across the meadow.

Big Meadows is known also for the Common Milkweed, which serves as the host plant for the Monarch butterfly and provides a backdrop for American Goldfinches that frequent the meadow in late July.

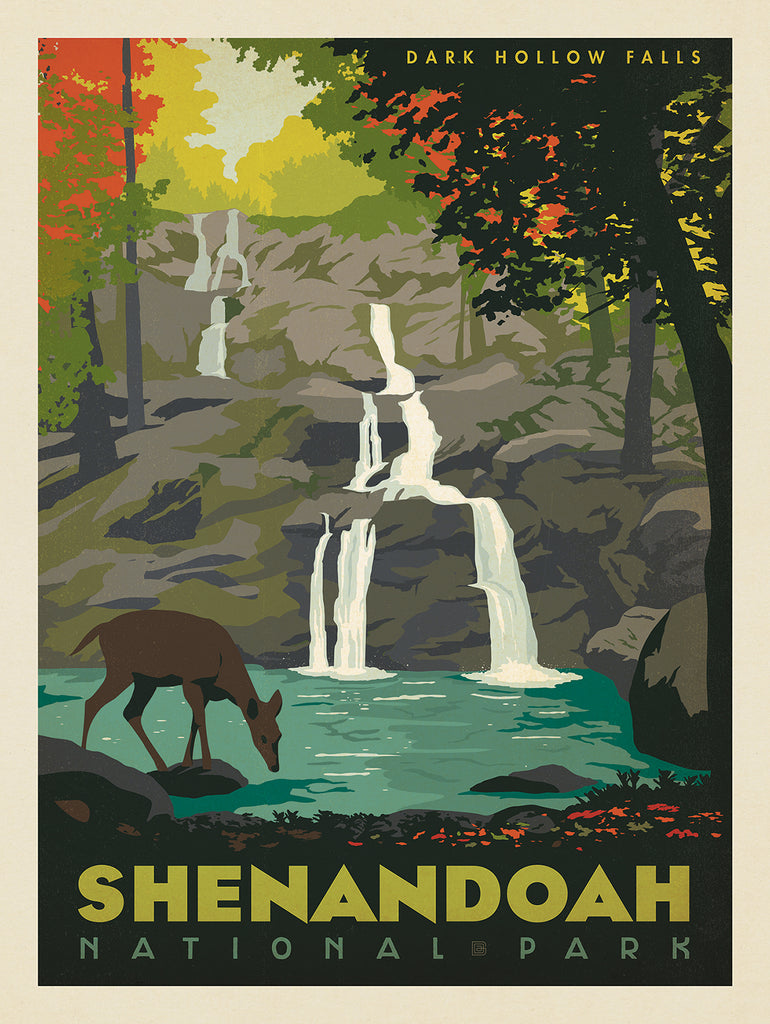

At milepost 49.5, just up the Drive from Big Meadows is the Fisher Gap Overlook, which provides the trailhead for the 4.5-mile Rose River Loop Trail, which descends down the eastern flank of the mountain along a stream until one passes by 67'-high Rose River Falls. Following the streambed leads to the more popular cascading waters of 70'-high Dark Hallow Falls. Though mostly uphill from this direction, the hike's end is an easy, gently uphill walk along a flat forest road until the Drive is reached again.

Near milepost 47, two of the park's iconic mountains can be viewed and visited. The nearby overlook provides a view of Old Rag (3268' elevation) to the east, but the real attraction is to the west up a gentle slope just under a mile away. Hawksbill Mountain is the highest peak in the park at 4,051', accessed via the Upper Hawksbill Trail that terminates at the Byrd's Nest 2 shelter and provides a magnificent view of the west.

Today, more than 40% of the park is officially Wilderness, the highest level of protection the nation can impart to land and its inhabitants, truly solidifying Roosevelt's promise to "re-create" the natural beauty of the area.

← Older Post Newer Post →